Once upon a time we trusted our bank managers. Once upon a time editors decided which news was important. Once upon a time we checked our facts using library reference books. Once upon a time we were confident in our major institutions.

Then the internet happened. Information became democratised and globalised. Citizen journalism took hold. Everything accelerated dramatically. Society became more networked. We began recording and sharing our experiences in real time. The ability to access information any time became ubiquitous.

The glow of a billion smartphone screens now helps illuminate the world around us. And some of us haven’t liked everything this has revealed. The banks, the church, journalism, the military, medicine, all of our great institutions now groan with strain.

As the illumination intensifies, in many ways citizens are coming closer together. You can now reach previously remote individuals from your dining table. You can gaze into people’s lives via social media. There is a world of data at your fingertips. You can grab tutorials when you want to learn something new or connect with your friends 24/7.

However, this illumination is also divisive. Some countries are still subject to enormous censorship. Non-stop, 24 hour news reporting leaves little time for contemplation. Mob rule can spoil social media. Images and voice are habitually manipulated. Information is used erroneously to back up dishonest arguments. False rumours spread fear fast and wide.

In fact these dangers have become so acute that the World Economic Forum, a group of top experts and thought leaders from around the globe, have highlighted the rapid spread of misinformation online as one of the “Top 10 trends of 2014.” The World Economic Forum wants world leaders to reflect on these important issues and collaborate to find new solutions – so that citizen connectedness continues to mean citizen closeness. The World Economic Forum cites four examples when making their case.

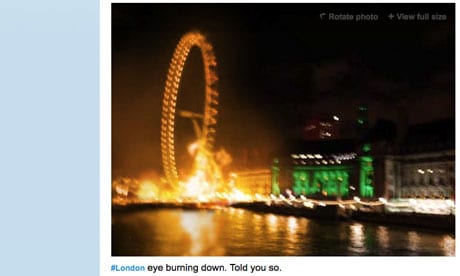

A fake photograph appearing to show the London Eye on fire which circulated on Twitter during the UK August riots.

- During the UK riots in the summer of 2011, a rumour spread on Twitter that a Birmingham children’s hospital had been attacked by looters. The story fitted with people’s preconceptions of who the rioters were and what they might be capable of and it caught the public imagination.

- During the US December 2012 Newtown shootings, online and mainstream media misidentified a Facebook page as that of the shooter.

- During the US April 2013 Boston bombings, social media users engaged in online detective work, examining images taken at the scene and wrongfully claimed that a missing student was one of the bombers.

- During the May 2013 Turkish protests that began with a plan to redevelop Taksim Square. Twitter ‘provocateurs’ were condemned as irresponsible for spreading misinformation, including a photograph of crowds at the Eurasia Marathon, which was presented as ‘a march from the Bosphorus Bridge to Taksim.’

As a PR professional, I see us as standing at the intersection between facts, data and image. With information and spokespeople being perceived as less reliable, we need to pinpoint the new language and behaviour of trust. We need to advise our clients on the virtue of transparency, consistency and values. We must remind ourselves of the codes of conduct we are signed up to with our employers and professional bodies.

It is vital that we understand the advantages and perils of a phenomenally connected audience. With the glow of smartphones only getting brighter, we must play our part in making sure connectedness brings people together.